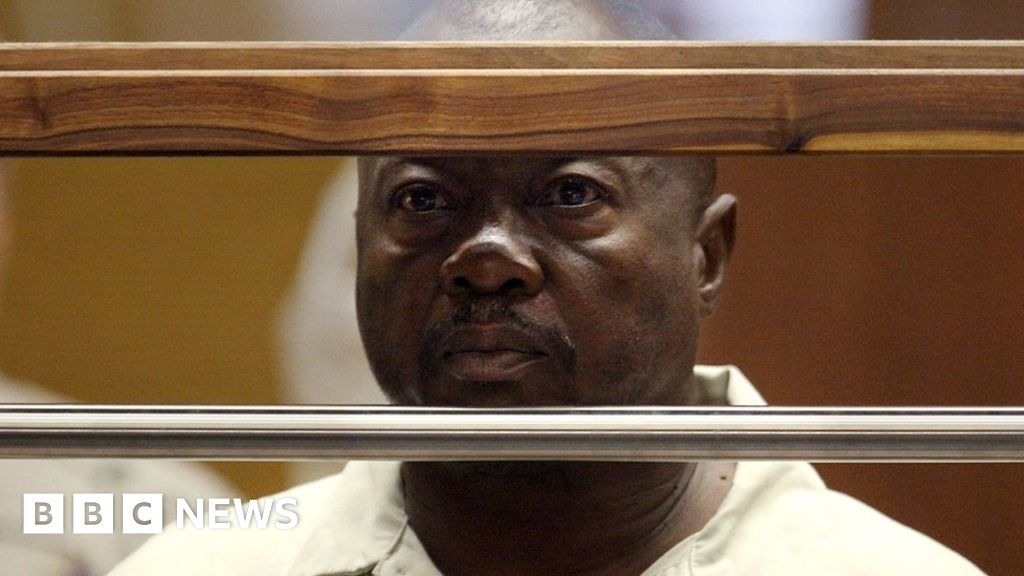

“The answer, of course, is yes.” Samuel Little, then 72, appears at Los Angeles Superior Court in March 2013. “Could it happen again today?” said Brad Garrett, a former FBI agent who has worked on some of the bureau’s highest-profile cases. criminal justice system: It is possible to get away with murder if you kill people whose lives are already devalued by society. By then, the killing was long over he has said his final victim died in Tupelo, Miss., in 2005.īut Little’s decades of impunity underscore a troubling truth about the U.S.

Advances in DNA technology and the rise of cold-case units eventually led to his arrest and conviction in 2014. He is locked up in a California state prison, serving multiple life sentences. Little, who also went by the name Samuel McDowell, did not respond to letters from The Post requesting an interview. But that’s not who he preyed upon,” said criminologist Scott Bonn, who has written extensively about serial killers. “If these women had been wealthy, White, female socialites, this would have been the biggest story in the history of the United States. In many cases, authorities failed to identify them as murder victims, or conducted only cursory investigations. What emerges is a portrait of a fragmented and indifferent criminal justice system that allowed a man to murder without fear of retribution by deliberately targeting those on the margins of society - drug users, sex workers and runaways whose deaths either went unnoticed or stirred little outrage. The Post also reviewed video and audio recordings of a number of Little’s confessions. To fill in the gaps, The Washington Post obtained and analyzed thousands of pages of law enforcement and court records - including a complete criminal history assembled in the early 2000s - and conducted interviews with dozens of police officials, prosecutors, defense attorneys and relatives of Little’s victims. The FBI has pleaded with the public for assistance but has declined to release Little’s case file, saying each murder investigation is being led by local authorities. Other cases remain in limbo, either because police have been unable to find a killing with circumstances to match Little’s description, or because the victim is an unclaimed “Jane Doe.”

So far, officials say they have identified more than 50 victims. And, with the fervor of an old man recalling the exploits of his youth, he has provided police with precise details about their murders, invariably effected by strangulation. Over more than 700 hours of videotaped interviews with police that began in May 2018, Little, now 80, has confessed to killing 93 people, virtually all of them women, in a murderous rampage that spanned 19 states and more than 30 years.Ī gifted artist with an unnervingly accurate memory, Little has produced lifelike drawings of dozens of his victims. (Obtained by The Washington Post)īy New Year’s Day 1971, Mary Brosley, 33, had become the first known victim of a man since recognized as the most prolific serial killer in U.S. “I just went out of control, I guess.” Authorities believe that Mary Brosley, a mother of two from Massachusetts, was Samuel Little’s first murder victim. Strong desires to … choke her,” he would later tell police. Little admired the way the moonlight illuminated her pale throat. Estranged from her family, struggling to survive, she was the kind of woman who might disappear from the face of the Earth without attracting much notice.

#South louisiana serial killer series#

The tip of her left pinkie finger was missing, sliced off in a kitchen accident, and she walked with a limp from hip surgery.īrosley said she had left a series of lovers and two children in Massachusetts after endless confrontations about her drinking. She was a frail, vulnerable woman, about 5-foot-4 and anorexic, barely 80 pounds. He’d met her at a nearby bar, drinking away the final hours of 1970. Before long, Mary Brosley had straddled his lap. Crime in baton rouge.Samuel Little guided his car to a stop in a secluded area off Route 27 near Miami and cut the engine.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)